"Shutter" Season: A summer with camera traps

Field sheets, AI in camera trapping, and then some!

Hello WildCAM Members!

I hope we’ve all been having a great time with the field season! I’m back, having survived the first round of camera checks here at the WildCo Lab. My updates for you include new field data sheets, a crash course intro to distance sampling (thank you Tristen Brush!), and of course, plenty of thoughts on the growing role of AI in camera trapping, among other exciting developments

Quick notes — WildCAM’s newsletters can now be found on our website too (wildcams.ca/news/newsletters). I’m also working on a new page annotating many of WildCAM’s introductory resources, so keep an eye out for that. For any questions or feedback, please feel free shoot me an email at info@wildcams.ca.

Let’s get into this!

Raunaq Nambiar, WildCAM Coordinator

⚠️ Membership Check-in ⚠️

A quick reminder — subscribing to the newsletter ≠ joining WildCAM. To join WildCAM, please visit wildcams.ca/join (or fill in the Account Creation form here).

🪪 Member Profile Updates

WildCAM Members get a shareable profile page on our website where their projects can be showcased. If you are a WildCAM member, please ensure to keep your profile details like your affiliations and projects up to date so that other members can be aware of your latest activities and work!

If you are having trouble signing in, please let me know at info@wildcams.ca. We’ve recently been having some trouble with email-related website issues (like password reset emails not being sent). If you’re experiencing these issues, please reach out to me and we can work out a fix!

🔄 Project Updates

I know I mentioned this in my last newsletter, so just briefly re-iterating it here for easy reference — you can update your projects on WildCAM using the form linked here!

Updated Materials: Deployment Sheets & Mammal ID Guide 📝

As the field season is underway, I thought it might be good to update our deployment and check sheets that are available for folks to use or modify for their projects! The 2025 updates are now available for use on WildCAM (wildcams.ca → Resources → WildCAM-developed resources → Field Documents and Set Up Guide).

I’ve also updated WildCAM’s mammal ID guide, and includes three new species — elk (Cervus canadensis), mountain goat (Oreamnos americanus), and bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis), as well as updated pictures and guidelines. The 2025 Mammal ID Guide is now available for use on WildCAM.

You can also find them here (check website for updated links as these documents keep being updated):

Deployment Sheet (2025 Version) — 1) PDF Version • 2) Google Doc

Check Sheet (2025 Version) — 1) PDF Version • 2) Google Doc

Mammal ID Guide (2025 Version) — 1) Google Doc

Join Us! – Postdoctoral Positions with WildCo 🧑🏽🔬

The Wildlife Coexistence Lab (WildCo) at UBC Vancouver is looking for 2 postdoctoral researchers! Helping build research capacity in the WildCAM Network, the positions will look at two key areas:

Density estimation of unmarked populations, and

Large-scale, multi-partner sampling designs

Application are being reviewed on a rolling basis, and more information on application requirements and submission details can be found on our website (wildlife.forestry.ubc.ca/people/join-the-lab) or in the position posting linked here.

So, you want to do distance sampling eh? 🫵📏

Looking to develop a study with camera trap distance sampling and don’t know where to begin? Well guess what — today is your lucky day. Developed by UBC WildCo Master’s student and WildCAM Member Tristen Brush, the video serves as an educational and approachable introduction to distance sampling.

The video can be accessed here, and is available under the WildCAM-developed Resources page along with a transcript of the video. All feedback is appreciated — you can send it over to me (info@wildcams.ca) or to Tristen directly (teb310@gmail.com)!

Project Spotlight 🌟

Big Bar Mesocarnivore Monitoring Program

Government of British Columbia

British Columbia has two populations of fisher (Pekania pennanti) – the Boreal and the Columbia populations. The latter was added to British Columbia’s red list in 2020, with disturbances like logging following forest fires being key drivers of the population’s decline. As part of the province’s mesocarnivore monitoring project, a camera trap survey was done to better understand fisher density and occurrence in the Big Bar area (Cariboo Region). The question — can collared fishers and camera traps yield sufficient data to run a spatial mark-resight analysis and estimate the density of this mesocarnivore?

The project set out to collar fishers and use telemetry data from the collars to run mark-resight density models. A quick word from WildCAM Advisory Committee member and provincial Carnivore Conservation Specialist Joanna Burgar on fisher collaring — “good luck!”. Fishers are low density carnivores, with home range sizes varying from ~ 30km2 (female) all the way up to ~80km2 (male). The time taken to travel their home range (2-3 weeks at times) lowers their detection probability (both by camera and through live traps). Add to this that collaring mustelids can be difficult with their slinky necks (i.e., too tight can rub at skin and too loose can hang them on branches as they move through trees) and the typical camera failures expected in a camera survey, and you have a project that ‘builds character’.

Lots of tracks in the area most certainly did not maketh a high detection camera spot, particularly given the low density and territorial nature of mesocarnivores like fishers. The project detected over 27 different species of mammals in the study area using 55 cameras with scent lures deployed between December 2023 and June 2024 (allowing for captures during the denning season from late March to early June). The BC Trappers Association assisted with pre-baiting live trapping sites. This project feeds into the government’s province wide integrated density modeling for the Columbian population of fisher and mesocarnivore species distribution modelling, as 11 mesocarnivore species were detected.

🆕 Wildlife in the News

⛰️ The end of Ontario’s Endangered Species Act

Earlier this month, Ontario passed Bill 5, a controversial piece of legislation that among other things, scrapped Ontario’s Endangered Species Act. Described during its release as “the gold standard for species protection”, the Endangered Species Act has now been replaced by the “Species Conservation Act”. The definition of “habitat” in the new legislation is as follows:

“habitat” means, subject to subsection (3) in respect of an animal species,

(i) a dwelling-place, such as a den, nest or other similar place, that is occupied or habitually occupied by one or more members of a species for the purposes of breeding, rearing, staging, wintering or hibernating, and

(ii) the area immediately around a dwelling place described in subclause (i) that is essential for the purposes set out in that subclause.

This definition has received considerable pushback from environmental groups. Another issue is the removal of the Committee on the Status of Species at Risk in Ontario’s (COSSARO) ability to independently add or remove species from the province’s SAR list (this authority has now been shifted to the government). British Columbia does not have provincial species-at-risk legislation. However, similar concerns to Ontario’s Bill 5 have been raised in lieu of the passage of Bill 14 and 15 by the BC government, which also allows for “provincially significant” projects to be expedited by cabinet.

🐈⬛ Cougar activity forces recreation trail closures in Garibaldi Lake and Whistler

Over the latter half of June, trails in the Garibaldi Lake area and Whistler have been closed on account of heightened cougar activity in the area. This includes simple sightings to cases of stalking and chasing. Possible reasons for this behaviour could include limited territory linked to human encroachment, and/or the cougar individuals possibly being injured.

Tension between humans and wildlife along recreational frontiers continues to be a policy challenge in British Columbia. From black bears to wolves, British Columbia’s rich biodiversity also means that the need for coexistence couldn’t be higher. WildCAM members more familiar with cougar behaviour — do you have any insights on this? Please send your thoughts and any relevant resources to me at info@wildcams.ca!

Papers of Interest 📖

🤖 Will the Last Person to Review Images Turn Out the Lights? — Reflecting on AI in Camera Trap Image Processing

It is a right of passage for every camera trapper to face a computer screen with an absurd number of images that need to be reviewed wondering if the stack of pictures ever ends. It makes sense then, that the growth of artificial intelligence (AI) in camera trapping has primarily been in the area of image processing. In their new opinion piece, Andrew Barnas and WildCAM Advisory Committee member Jason Fisher (2025) reflect on this, and highlight both the gains to be made, and potential losses that must be considered as AI only continues to gain steam.

The rapid processing of large volumes of images promises vast savings in time and money — both of which are very useful commodities in a research economy. However, is this gain worth the trade off? Manual image review helps train junior staff and students and is a key step in the camera trap research pipeline. It also allows for novel observations and discoveries to be made that may be outside the scope of the initial review (and thereby unnoticed by a hypothetical AI review). It’s also a driver of human-wildlife connections — the kind that the foundation of wildlife conservation is built on. Can we still preserve that?

Veteran Seattleites will recognize the reference in the title of this section — it’s from a billboard put up in 1971 referencing the economic misfortunes of the city during a recession when many left Seattle.

"Artificial intelligence tools are going to continue to improve, and we will rely on them more and more for camera trap image classification. We need pragmatic solutions on how we can use AI for camera trap image classification and maintain personal connections with wildlife research." — Andrew Barnas

🕵️ Will the real driver(s) of caribou decline in the Chicotins please stand up?

It feels logical — Logging triggers a pulse of new growth → consumers of said growth come in to eat → consumers of consumers subsequently come in → caribou pay the price. The word for this flowchart is DMAC — disturbance-mediated apparent competition.

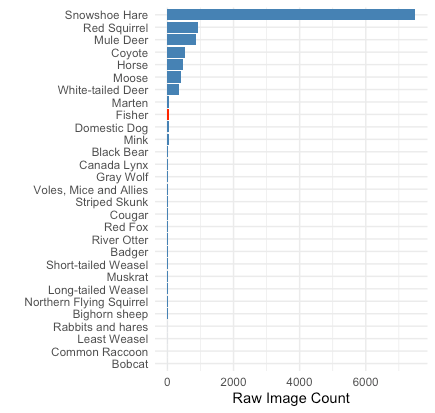

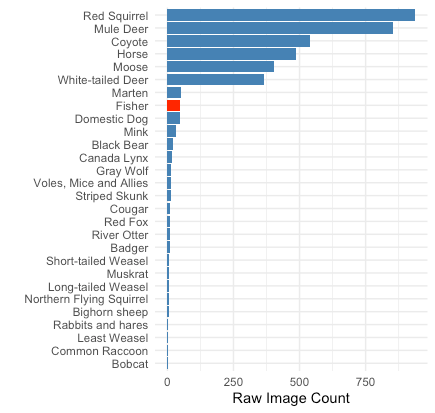

However in Tjaden-McClement et al. (2025), as usual, the real data doesn't fit in so neatly. Using 179 cameras across 6 grids, over 1.8 million images (yielding 8,778 independent detections of focal species) were collected from in and around Itcha-Ilgachuz Provincial Park.

Looking at prey ungulates like moose and mule deer, it was fire that seemed to more strongly predict their presence than cutblocks and roads. They had a 213% and 482% increase respectively in predicted detections between burnt and unburnt areas. At the predator stage, however, things get murky. For instance, it was snowshoe hare, not mule deer or moose, that wolves had the strongest association with. Predators like wolverine showed no strong positive response to any ungulate prey. With caribou, during non-calving times at low elevation, they were found to be weakly but positively predicted by cutblocks/roads (which is a possible issue given that predators like black bears are also positively related to cutblocks).

Long story short, it’s complicated. DMAC is at play, but it doesn’t explain everything. It takes a lot to figure out why a population of ~2,800 in 2003 became ~358 in 2019. It’s cutblocks, but it’s also fire. It’s predators being attracted to increased prey numbers, but also linear features like roads facilitating predator movement. It’s moose, but also snowshoe hares and maybe even feral horses. Death by a thousand drivers, if you will.

“Overall, this study reinforces calls for context-specific research and adaptive management to determine what conservation actions will have the greatest benefit for different caribou populations, including those in low-productivity areas.”

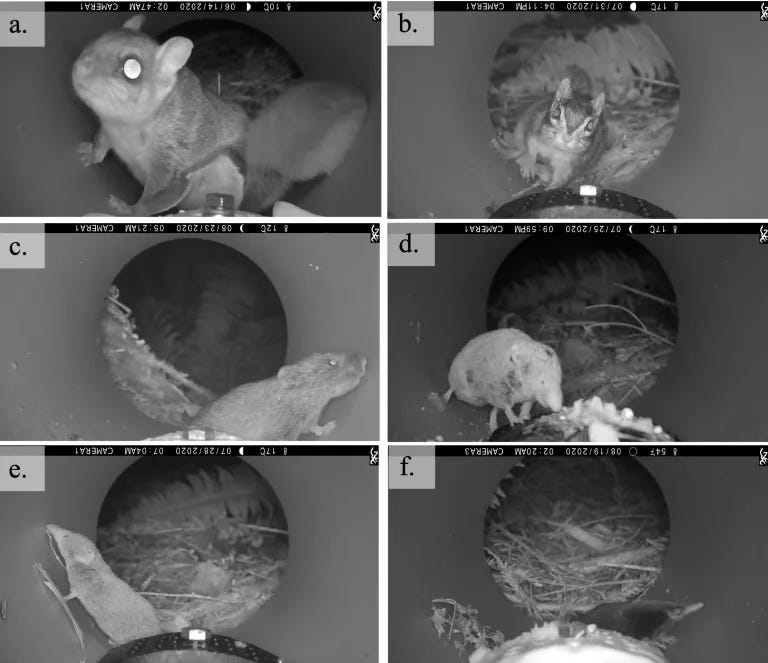

🐭 A (pipe) dream come true — small mammal monitoring using PVC pipes

Pipe, Camera, Action! That’s the methodology Clucas & McCluskey’s (2025) paper investigating small mammal diversity in northwestern California. Borrowing the design from Gracanin et al. (2019), a camera was placed at one end of a PVC pipe, looking through the pipe out the other end, where bait awaits. Using a 4x Zoom Lens, the projects looked for two results — could this really work for detecting small mammals, and is it resilient to interference by larger mammals?

So, did sticking peanut in a bait container and positioning a camera inside a PVC pipe work? Wouldn’t it be really funny if I said no and that’s where the summary ends?

Anyways it did! 10 different small mammal species (out of the 13 that are known to be present in the Headwaters Forest Reserve where the project took place) were detected. The set up also withstood recorded interactions with larger animals like fishers and black bears. Camera set ups involving tubes have also been used on larger mammals like polecats (Mustela putorius) (Hofmeester et al., 2024), and indeed fishers (Pekania pennanti) and even black bears (Ursus americanus) were observed at the cameras. Sometimes tunnel vision ain’t too shabby!

Photo 🎞️

So…turns out I’ve completely run out of space for actually putting in more photos. As an offering, I would like to give you one absolutely excellent caribou photo from the Chilcotins. Till the next letter!